Reuters columnist Jamie McGeever looks at the potential impact of an inverted U.S. treasury yield curve.

- An inverted U.S. Treasury yield curve almost always heralds recession, but the yawning gap between high short-term funding costs and falling long-term borrowing rates may accelerate the economic downturn it presages.

- From a banking sector perspective, the inverted curve, combined with near-9 percent inflation and post-2008 regulation – the deepest, highest, and toughest in decades, respectively – offers cause for concern.

- Although banks are in pretty good shape, the downward-sloping curve will erode net interest margins and curb lending, while this year’s rout in stocks and bonds will require them to divert more cash towards repairing torpedoed capital buffers.

For more data-driven insights in your Inbox, subscribe to the Refinitiv Perspectives weekly newsletter.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.

All things equal, the economic impact of banks reducing credit to businesses and households can only be negative.

Banks can make money when interest rates rise but this is far easier when the yield curve slopes upward, and they borrow lower and lend higher. A deeply inverted curve puts a damper on margin expansion.

“The slope of the curve matters,” says Christopher Wolfe, Managing Director, North American Banks at Fitch Ratings in New York.

Wolfe notes that bank loan growth accelerated and net interest margins expanded in the second quarter on the back of continued Fed tightening. But although the yield curve compressed and briefly inverted in April-June, it was still mostly positive sloping.

Not any more.

Two hundred and twenty-five basis points of rate hikes this year and the promise of more to come as the Fed battles to bring inflation somewhere in the same ZIP code as its 2 percent target has lifted the two-year yield almost 50 bps above the 10-year yield.

This is the deepest inversion since 2000, although it retreated to 40 bps on Wednesday after softer-than-expected inflation data for July.

According to Bank of America analysts, if the Fed’s ‘terminal rate’ ends up being more than 4 percent – i.e, some 50 bps higher than current market pricing suggests – then the yield curve could invert by as much as 85 bps.

That would be the deepest inversion since the savage Volcker-triggered recession of 1981.

Recession now?

Of course, a debate is currently raging on whether the U.S. economy is already in recession. GDP output shrank in the first and second quarters this year, in real terms, meeting the technical definition of recession.

But many economists reckon strong nominal growth and a red-hot labor market – average job growth this year is running at almost 500,000 a month – will steer the National Bureau of Economic Research away from calling the current blip a full-blown recession.

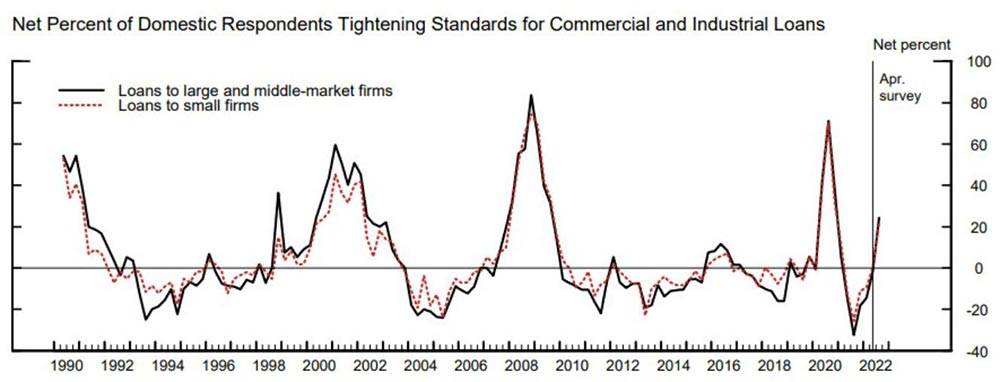

However, banks are beginning to draw in their horns. The Fed’s latest Senior Loan Officer survey shows that a “significant” net 24 percent of banks tightened lending standards for commercial and industrial loans in July.

The figure for big banks was even higher at 26.5 percent.

The survey showed banks are doing this by charging higher premiums on loans, widening lending spreads, or toughening up collateral conditions. As the Fed continues to tighten, so will these lending conditions.

Banks’ second-quarter profits slumped as they set aside more cash to cover potential loan losses. Provisions approached $10 billion in the period, and according to Christopher Whalen of Whalen Global Advisors, will return to around $20 billion a quarter before a “credit reckoning” comes to the fore.

It is worth noting that during the last two recessions of 2007-09 and 2020, banks’ loan provisions topped $60 billion a quarter.

On top of that, the sharp rise in interest rates this year has meant banks have had to write down the value of fixed-income securities in their portfolios. This has been particularly painful because the rout was so severe – one of the worst in decades.

Morgan Stanley’s Betsy Graseck estimates that the three largest U.S. banks alone – JP Morgan, Bank of America and Citi – may need to reduce their risk-weighted assets by more than $150 billion by the end of this year.

It’s another painful pressure point that is likely to persist as long as the yield curve is heavily inverted, markets are fragile, and recession looms large over the economy.